Twist in the tale: Clarion Island's iguanas pre-date human presence

In a discovery reshaping our understanding of Pacific island ecology, an international team of researchers has revealed that the spiny-tailed iguanas inhabiting Mexico’s remote Clarion Island are not human introductions after all.

In a discovery reshaping our understanding of Pacific island ecology, an international team of researchers has revealed that the spiny-tailed iguanas inhabiting Mexico’s remote Clarion Island are not human introductions after all – but ancient natives that have inhabited the island for nearly half a million years.

The study, led by biologists from the Natural History Museum in Berlin alongside a cohort of international collaborators, used DNA evidence to show that the Clarion spiny-tailed iguanas (Ctenosaura clarki) diverged from their mainland relatives around 425,000 years ago.

This discovery has therefore placed the species on the island long before humans ever reached the Americas.

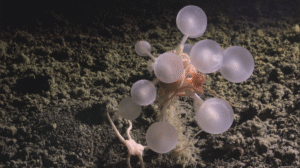

Clarion Island is the oldest of the volcanic Revillagigedo Archipelago off Mexico’s Pacific coast. It’s a rugged, isolated world formed about five million years ago that – much like the Galápagos and Hawaiian Islands – has never been connected to the mainland. Despite this, it has been naturally colonised over millennia by birds, snakes, and lizards that managed to cross vast ocean stretches, most likely by rafting on floating vegetation.

But human arrival in the 20th century brought sweeping ecological change. In the 1970s, the Mexican military established a base on the island and introduced sheep, pigs, and rabbits, which quickly stripped away native vegetation once described as “impenetrable with prickly pear cactus.”

As the dense cover vanished, shy spiny-tailed iguanas – previously hidden in burrows and rocky crevices – suddenly became visible.

However, since earlier expeditions from the late 1800s to the mid-1900s had not reported the species, scientists assumed these reptiles had been introduced along with other livestock. Consequently, Clarion’s iguanas were targeted for eradication under wildlife management programs aimed at removing non-native species.

The new genetic study now challenges that long-held assumption. By comparing DNA sequences from a Clarion specimen with mainland iguanas, researchers used Bayesian evolutionary analyses to estimate the iguanas’ separation from their continental cousins to roughly 425,000 years ago.

To put that into context, humans are believed to have first reached the Americas around 16,000 to 26,000 years ago – hundreds of thousands of years later.

This timeline points strongly to what scientists call a natural overwater dispersal, rather than through human introduction. The study suggests that iguanas likely arrived on Clarion via floating vegetation, much like other reptile and bird species that colonised the island chain.

The revelation has, of course, immediate implications for conservation policy. With the island’s introduced sheep and pigs already eradicated and rabbit control ongoing, management plans that included removing the iguanas will now be revised.

“This research fundamentally changes how we view Clarion’s ecology,” said the team. “The spiny-tailed iguana is not an invader – it’s a survivor.”

The study also underscores the critical role of museum collections and genetic research in informing conservation strategies. Specimens preserved decades ago provided the DNA necessary to unravel the iguana’s deep evolutionary history – evidence that may well save a species from unnecessary eradication.

Clarion’s iguanas now join the island’s impressive roster of native wildlife, which includes endemic snakes, lizards, and numerous bird species. For scientists studying island biogeography, the discovery adds another piece to the puzzle of how life disperses, adapts, and endures across the world’s most isolated ecosystems.

"*" indicates required fields

Printed editions

Current issue

Back issues

Back Issues

Issue 43 Sir David Attenborough’s ‘Ocean’

Back Issues

Issue 41 Holdfast to the canopy

Enjoy so much more from Oceanographic Magazine by becoming a subscriber.

A range of subscription options are available.