Meet me in Misool: The jewel and duality of Raja Ampat

While Misool and the larger Raja Ampat is a place of unparalleled this jewel of Indonesia has another side that often goes minimally discussed by those within the diving community. There’s the underbelly that not a single paradise can escape in our modern times.

Getting around Raja Ampat, Indonesia means you’re going to get wet. Here, instead of cars, there are boats; instead of clothes, sub in wetsuits. The villages that line these islands rely entirely on the ocean for food, income, transport, sport and community.

Here, life is peaceful. Envision children carrying their chickens along the wooden boardwalks and families gathered for their daily routines – time moving in slow motion. From above, Raja Ampat is even more striking than you’d expect – emerald-green karst islands scattered across a vast, turquoise-to-deep-blue sea, fringed by reefs that look anything but modern.

It’s no wonder this is one of the last remaining coral paradises of its kind – a place so many of us thalassophiles dream of exploring.

Raja Ampat’s name (translated to Four Kings) was derived from legend whereby four islands were bestowed upon the kings of this region. But the depth of Indonesia’s east goes well beyond just this storied name. This region is an expansive marine protected area network made up of seven MPAs, with the southernmost island, Misool, being arguably the most coveted, according to the Marine Conservation Institute that studies MPAs. Because of this sprawling network, you’ll find yourself surrounded by two types of people when touching down in Sorong, the port hub that connects the entire Raja Ampat: locals and divers.

Since the very start of our expedition around the world, our sights were set on heading to Raja Ampat’s south. Its remoteness makes it one of those unrivaled marine frontiers, with an infrastructure far from established. Electricity is used sparingly, hot water is virtually nonexistent, and when the storms roll in, you’re likely to succumb to the elements.

But this is all part of the south’s magic. Life is dictated by the ocean’s movements, and connection with nature is everything. For divers, this is the true pinnacle of the sport.

But, becoming one of those visiting divers here isn’t guaranteed. Survival is a struggle on this archipelago within an archipelago. For all its dazzling colors, thriving reefs, and endless variations of sambal (Indonesia’s beloved chili, lime, onion, and garlic condiment), Misool, and the larger Raja Ampat for that matter, has another side that often goes minimally discussed by those within the diving community. There’s the underbelly that not a single paradise can escape in our modern times.

As is true on many remote islands, waste management is a glaring issue, having no viable means of large-scale waste removal. So where does it go? Either it’s burnt or cast straight into the ocean. Local champions do what they can, organising clean-ups along the shorelines, but even then, the efforts are often futile.

Then there’s the illegal fishing within protected areas. No matter how remote, this is a global issue that’s plaguing many of our most resource rich places. This is contributing to the larger overfishing problem that is depleting critical stocks, threatening food security, livelihoods, and marine ecosystems.

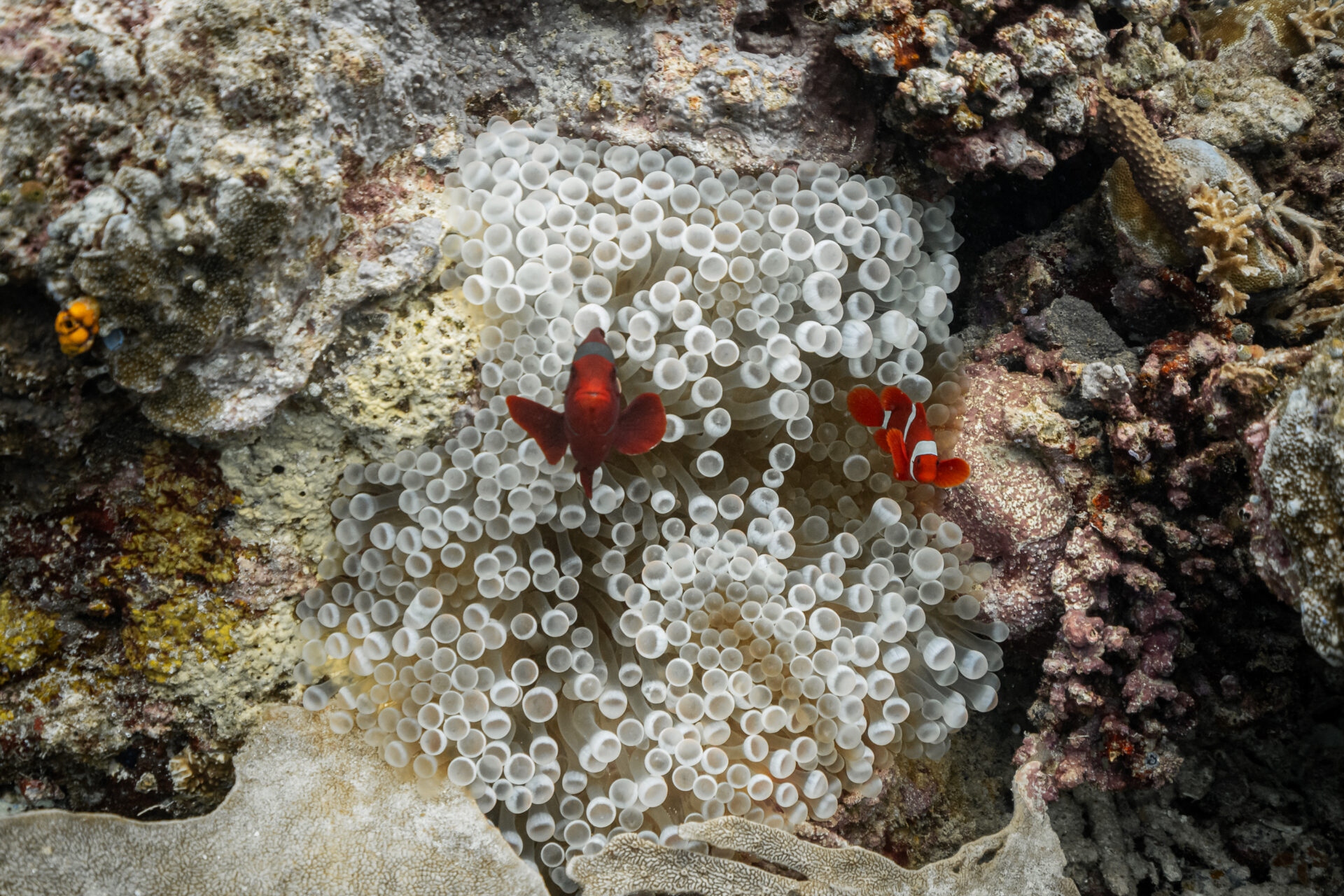

And beyond that, reef degradation and bleaching from human impact and climate change is taking a toll. Seeing entire swaths of reef reduced to rubble is heartbreaking for anyone passing through Indonesia, with local communities feeling the implications the hardest. No reefs mean no food, no income, no tourism – the very industry Raja Ampat now depends on.

There’s always a duality in places like this. There’s the surface-level beauty of rock formations, glowing reefs, and crystalline waters. And then there’s the reality of an ecosystem under extreme pressure, unraveling slowly and undeniably. Survival hangs in the balance, relying on the individuals and teams working tirelessly to hold the line.

Pulling up to Yellu Village, the gateway to southern Raja Ampat, we prepared to live alongside the Misool Foundation team, immersing ourselves in how they manage one of the largest biodiversity hotspots in the region.

And after years of commitment, the Misool Marine Reserve has become a global model for marine conservation. What began as a strict enforcement effort to stop illegal fishing has since evolved into a powerhouse initiative spanning reef restoration, waste management, community development and species reintroduction. By working across all critical sectors – from tourism, nonprofit, government, and local communities – the Foundation has helped increase fish biomass by over 250% since monitoring efforts began in 2007, proving that their integrated, holistic and always-on approach actually works.

Managing such an expansive reserve takes an army, and we were slowly getting introduced to all of the leading figures that are behind this positive progress. The first group we encountered was the ranger team, also known as the Misool Marine Reserve’s frontline defense. Across three strategically placed ranger stations – Kalig, Yellit, and Daram – 18 rangers work in rotating shifts to monitor and protect these waters.

While illegal fishing has decreased significantly since the rangers presence and long enforcement fight here, smaller non-commercial fishers continue to push into protected zones, forcing rangers to take a persistent but diplomatic approach.

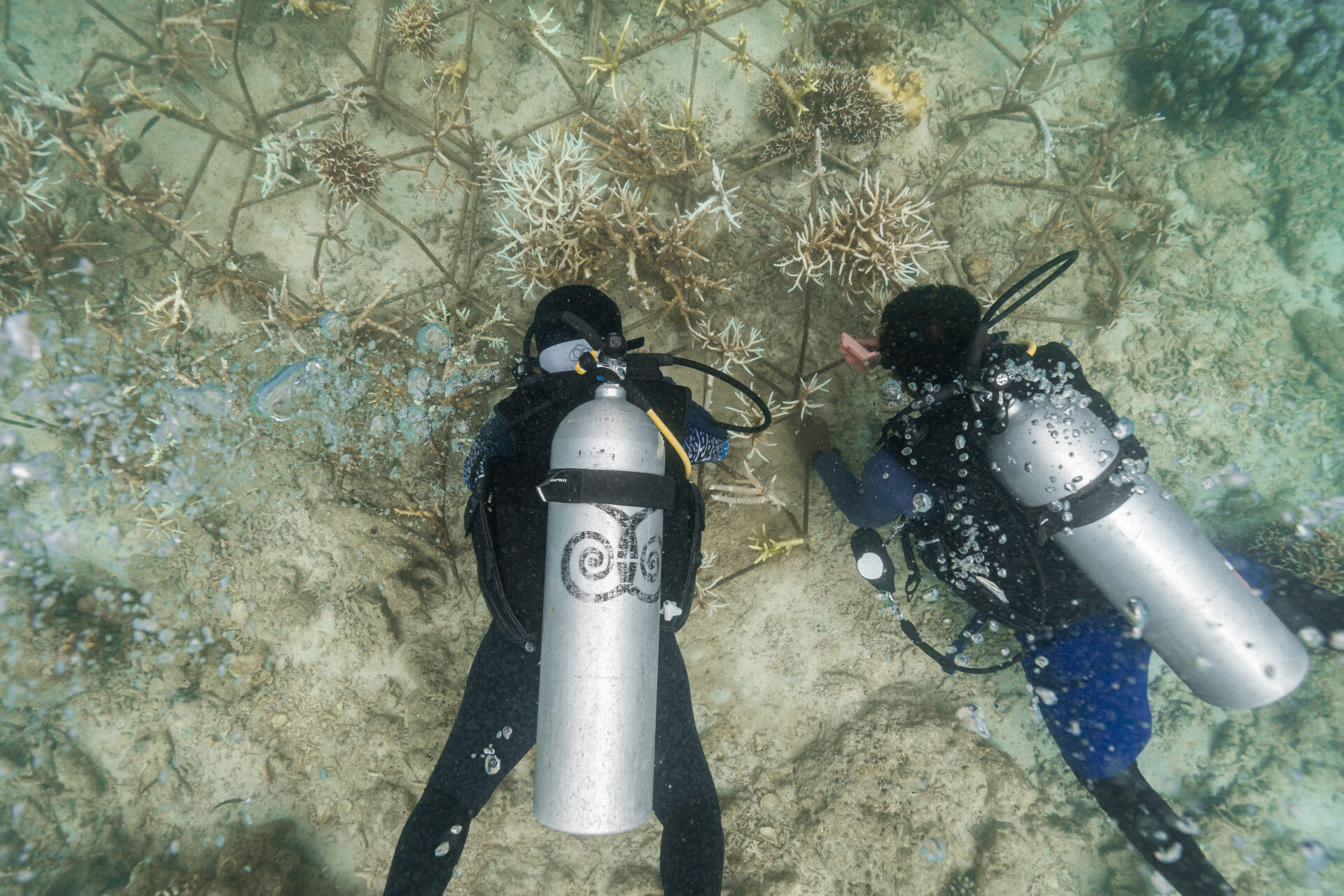

Today, the ranger and restoration teams are focused on another vital initiative, albeit more recent: restoring what’s been lost. The Reef Restoration Project is using its manpower to identify the best techniques to rebuild damaged coral reefs and revive habitats impacted by overfishing, destructive fishing, and climate change. We visited one of their restoration sites just outside the Kalig ranger station, where barren patches of reef have been transformed into thriving ecosystems again.

Dropping down to 5-10 meters, we were stunned. The restoration sites were pulsing with life – a profound sight in all of its multicoloured splendour. In some places, it was hardly perceptible that these were a construct of human intervention. Years of diligent work had gone into rebuilding these sites, fighting against mounting challenges every step of the way. After hours of diving, it was hard not to find ourselves thoroughly impressed at the scale, scope, and health of this rebuilt reef system.

After one of our dives, while regrouping on the surface, Murid Saleo, the Foundation’s lead reef restoration specialist, said, “I think about my children – the reefs I’ve built. I worry for them.”

Murid has been the driving force behind this restoration work and looks at every single piece of coral as part of him. All the while, he’s been tracking ocean temperatures, and to him, the data is alarming. What once hovered around 27-28°C now consistently spikes to 29-32°C, an unprecedented shift accelerating the risk of coral bleaching.

Compared to the start of 2023, conditions have deteriorated, and across the MPA network, reports of bleaching are increasing—a warning for what’s to come in Raja Ampat’s future.

Just before our arrival, a mass bleaching event struck the northern reefs of Raja Ampat, devastating some of its most iconic dive sites. While Misool was spared this time, it still hit far too close to home. Many of the Foundation’s team members, like Murid, have seen what happens when marine ecosystems collapse. Having worked in heavily degraded waters elsewhere, they know what’s at stake.

Murid said, “Here, I see what’s possible. And I want more people to understand that. I want more of us to take action and more visitors to understand the deeper story here.”

Despite the challenges, this team remains relentless. Regular reef monitoring is an ongoing effort – removing encroaching algae, controlling coral predators like crown-of-thorns starfish, and preventing human-driven damage, including waste dumping that appears to be from passing liveaboards.

While the rangers haven’t caught offenders in the act, they’ve discovered plastic waste accumulating at key liveaboard mooring sites, clear evidence that some boats are still discarding trash at sea.

This reality was truly baffling to us. As divers, we have a genuine responsibility when it comes to cleaning up the ocean and keeping places as special as this pristine for those who come next. The patrol team’s response is one of prevention through education and remaining calm all the while – working closely with operators to make sustainability a shared responsibility rather than an afterthought.

Each day, no matter where we explored, we always came back to Yellu Village. What made this place so significant was the village’s desire and determination to take conservation into their own hands. After seeing the reef restoration efforts at Kalig Station themselves, a small group of villagers realised they wanted the same regrowth for their home reef.

While we’ve seen many conservation teams and foundations push these efforts onto local villages, this time, the desire came from the community itself. It was their vision for change.

Ten men from Yellu stepped forward to lead the effort after realising how degraded their home reef was in comparison to the ranger station. They had watched how restoration was reviving ecosystems elsewhere in Misool and understood what that could mean for their own future.

Their village chief reached out to Misool Foundation initially, and soon, they were recruiting others to join the mission. The reefs around Yellu had been struggling—battered by shifting weather patterns, extreme low tides, and outbreaks of crown-of-thorns starfish. The shallowest corals were exposed to the scorching sun, only to be hit by heavy rainfall—a lethal combination.

When speaking with the community leaders driving this effort, they shared a pivotal decision made 20 years ago, and one that changed everything. Back then, dynamite fishing was common practice, a method they now recognise as destructive. As tourism in Raja Ampat grew, the community realised a living reef was far more valuable than a dead one and blowing up their fish stocks was not a sustainable pathway for the future.

They made the choice to stop bombing, and now, a few of the very men who once participated in it are at the forefront of bringing back the same reefs they once destroyed.

Murid and his team had tested three different artificial reef methods across Misool, restoring over 5,000 square meters of coral habitat at 10 key sites since 2018. Yellu Village’s very first restoration site is using a method called “webbed restoration,” a spider web-like structure designed to support coral fragments as they grow. This pilot project covered 80 square meters, and in just one year, the positive results were undeniable.

Diving off the boardwalks of our newfound home, we saw what the community leaders meant when they said 80% of the coral had survived despite recent surging storms. The webbed structures that sat at around 5-6 meters were continuing to see growth since their installation in June 2024. New coral recruits had naturally settled onto the structures, and bleaching was minimal. But one of the most promising signs was the return of the native fish populations. What was once a barren patch of ocean was now far from it, proving what’s possible when a reef is given the chance to regenerate.

Each of these men has a direct tie to tourism, working as either guides, boat operators, or homestay owners, meaning they all depend on a healthy marine ecosystem sitting right at their boardwalks. They shared their thoughts about how a healthy reef is just as much about biodiversity as it is about their future, their livelihoods, and the sanctity of their home.

While the broader community supports the project, it’s this small, dedicated team of scuba and freedivers who are leading the charge, becoming the champions of their village’s underwater world. The people were proud, stating that if this first site is any indication of what’s possible, Yellu’s reefs are surely on their way to a much larger recovery.

Raja Ampat is a place that feels like a relic of a wilder, more abundant ocean. A rare glimpse into what once was and, and with the right effort, what could still be. But paradise isn’t self-sustaining, at least not today. It takes work, commitment, and a willingness to evolve.

The future of these waters doesn’t rest solely in the hands of conservation organisations or scientists – it belongs to the communities that call this place home, to the divers who come here in awe, and to all of us who understand what’s at stake.

The men of Yellu, the rangers patrolling Misool’s waters, the teams rebuilding reefs – each of them is living proof that change is possible when people decide to fight for what matters most. For Raja Ampat, the work is far from over. But if there’s anywhere left on Earth that shows us why protecting the ocean is worth it, there’s no question that it’s right here.

Printed editions

Current issue

Back issues

Back Issues

Issue 43 Sir David Attenborough’s ‘Ocean’

Back Issues

Issue 41 Holdfast to the canopy

Enjoy so much more from Oceanographic Magazine by becoming a subscriber.

A range of subscription options are available.