Australia’s marine havens on track for 'extreme' conditions by 2040

A recent study led by the University of the Sunshine Coast, has found that by 2040, ocean conditions once deemed 'extreme' will become the new baseline across much of Australia’s marine estate - including within carefully managed Marine Protected Areas.

Even Australia’s most protected marine sanctuaries are on course to experience extreme ocean conditions within the next two decades, according to new research that paints a stark picture for the nation’s marine biodiversity.

A study led by the University of the Sunshine Coast (UniSC), published in Earth’s Future, has found that by 2040, ocean conditions once deemed ‘extreme’ will become the new baseline across much of Australia’s marine estate – including within the country’s most carefully managed Marine Protected Areas.

“This unprecedented scenario will create warmer, more acidic waters with reduced oxygen levels, and will expose ecosystems to more frequent and intense marine heatwaves,” said lead author Alice Pidd, a PhD researcher in quantitative marine ecology at UniSC.

The research team modelled future ocean conditions under a range of climate scenarios, including a conservative global temperature rise of 1.8°C this century. Even under that lower-end projection, the findings suggest that Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) will face similar levels of vulnerability as unprotected ocean zones – a troubling revelation for regions established to safeguard marine life.

“It’s the first comprehensive assessment of climate change exposure across Australia’s entire marine estate,” explained co-author Professor David Schoeman of UniSC. “And unfortunately, the results are not surprising. Marine Protected Areas will not be immune to the effects of warming, oxygen loss, acidification and heatwaves.”

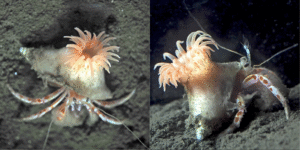

MPAs currently encompass around half of Australia’s seven million square kilometres of marine territory, protecting coral reefs, kelp forests, seagrass beds and mangrove ecosystems. Yet, as Pidd has noted, these zones were designed primarily to mitigate human impacts such as fishing, mining and shipping and not to withstand a rapidly changing climate.

“Their location alone won’t shield them from climate-driven changes,” Pidd said. “MPAs in north-western and eastern Australia appear most at risk.”

Co-author Associate Professor Kylie Scales, who supervised the research, highlighted the importance of these areas as biodiversity strongholds supporting whales, sharks, turtles and commercially valuable species such as tuna and billfish.

The loss of resilience in these ecosystems could ripple across both conservation and fisheries sectors.

The authors have since called for urgent and aggressive emissions reductions to slow the projected impacts. While Australia’s pledge to cut emissions by 62–70% by 2035 marks progress, Pidd said the commitment “is a good start but not enough to reverse the trends we describe.”

The researchers have gone on to warn that even with rapid carbon cuts, widespread change is inevitable. Some marine refuges could begin to recover after 2060 – but only if global emissions are drastically curtailed in the coming years.

“We’ve already crossed several climate tipping points,” Pidd added. “Biodiversity will need to adapt. To give it the best chance, we recommend designing climate-smart MPAs that are robust to future ocean conditions.”

The findings have echoed global patterns of ocean change, underscoring the urgency of new international protections such as the United Nations High Seas Treaty, due to enter into force in January 2026.

“The past is no longer a reliable guide to the future,” he said. “But with the High Seas Treaty enabling MPAs beyond national waters, there’s reason for cautious optimism – provided the world keeps this momentum.”

"*" indicates required fields

Printed editions

Current issue

Back issues

Back Issues

Issue 43 Sir David Attenborough’s ‘Ocean’

Back Issues

Issue 41 Holdfast to the canopy

Enjoy so much more from Oceanographic Magazine by becoming a subscriber.

A range of subscription options are available.