Colossal squid filmed alive on camera for first time ever

On the 100th anniversary of the very first discovery of the colossal squid, researchers have finally - and for the first time in history - captured video footage of the deep-sea giant alive and in its environment, marking a significant moment for ocean research and exploration.

One hundred years after its first discovery, the colossal squid has finally been filmed alive in its environment for the first time – quelling the thirst but stoking the fire of imagination for deep-sea researchers across the globe.

What’s more, the colossal squid that has been filmed… is only a baby, measuring in at 30-centimetres (nearly one foot long) – a fraction of the size it will grow to when this juvenile reaches adulthood.

So, who’s to thank for bringing this footage from the depth of the ocean to light (and on the 100th anniversary of the formal identification and naming of the colossal squid, no less)? Well, that would be a team of international researchers on board Schmidt Ocean Institute’s renowned research vessel, the Falkor (too).

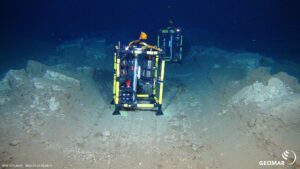

The sighting occurred on March 9 this year on an expedition near the South Sandwich Islands in the South Atlantic Ocean and captured at a depth of 600 metres by the Institute’s remotely operated vehicle (ROV) SuBastian.

“It’s exciting to see the first in situ footage of a juvenile colossal and humbling to think that they have no idea that humans exist,” said Dr Kat Bolstad of the Auckland University of Technology, one of the independent scientific experts the team consulted to verify the footage.

“For 100 years, we have mainly encountered them as prey remains in whale and seabird stomachs and as predators of harvested toothfish.”

It was the latest in a spate of significant sightings, following an expedition on January 25 this year when researchers filmed the first confirmed footage of the glacial glass squid (Galiteuthis glacialis) in the Southern Ocean near Antarctica.

Like the colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamilton) the G. glacialis belongs to the glass squid family (Cranchiidae) and had too – until now – never before been seen alive in its natural environment.

The 35-day expedition that captured the footage of the colossal squid was an Ocean Census flagship expedition searching for new marine life – a collaboration between Schmidt Ocean Institute, the Nippon Foundation-Nekton Ocean Census, and GoSouth – a joint project between the University of Plymouth, GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research, and the British Antarctic Survey.

Colossal squid are estimated to grow up to seven metres in length and can weigh as much as 500 kilogrammes, making them the heaviest invertebrate on the planet. Little is actually known about the colossal squid’s life-cycle, but that eventually they lose the see-through appearance of the juveniles.

Dying adults have previously been filmed by fishermen, but have never been seen alive at depth.

One of the most distinguishing characteristics of colossal squid is the presence of hooks on the middle of their eight arms, which help differentiate them from G. glacialis. Other than this, juvenile colossal squid and G. glacialis are very similar, with transparent bodies and sharp hooks at the end of their two longer tentacles.

“It’s incredible that we can leverage the power of the taxonomic community through R/V Falkor (too) telepresence while we are out at sea,” said the expedition’s chief scientist Dr Michelle Taylor of the University of Essex.

“The Ocean Census international science network’ is proud to work together with the Schmidt Ocean Institute to accelerate species discovery and expand our knowledge of ocean life, live online with the world’s science community.”

To date. The Schmidt Ocean Institute’s ROV SuBastian has captured the first confirmed footage of at least four squid species in the wild, including the Spirula spirulina (Ram’s Horn Squid) in 2020 and the Promachoteuthis in 2024, with one more fist sighting still to be confirmed.

Dr Jyotika Virmani, Schmidt Ocean Institute’s executive director, said: “These unforgettable moments continue to remind us that the Ocean is brimming with mysteries yet to be solved.”

"*" indicates required fields

Printed editions

Current issue

Back issues

Back Issues

Issue 43 Sir David Attenborough’s ‘Ocean’

Enjoy so much more from Oceanographic Magazine by becoming a subscriber.

A range of subscription options are available.