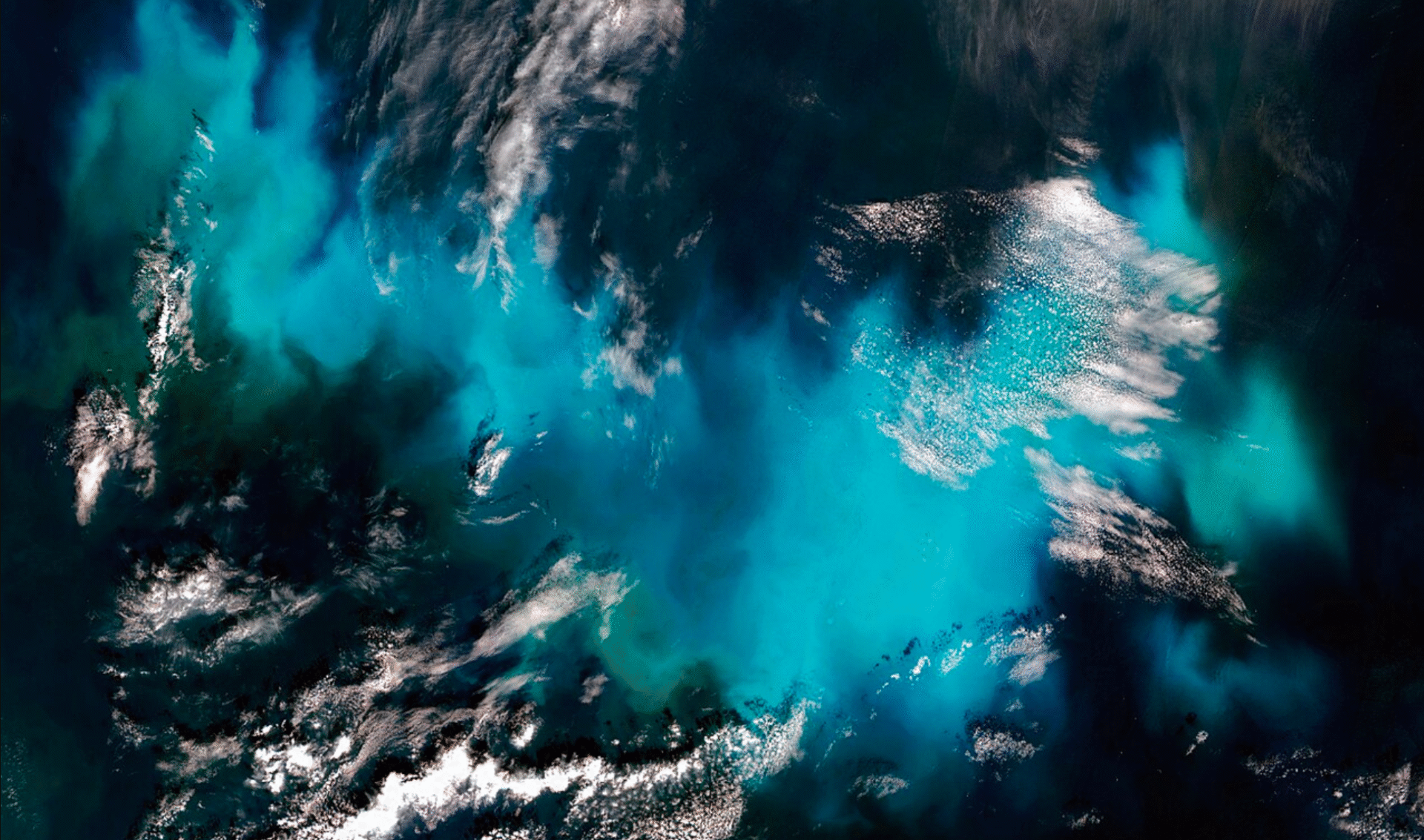

Ocean 'greening' at its poles means changes afoot for fisheries

Analysing recently published satellite data, scientists have warned that if this trend of ocean greening towards the poles continues, marine food webs could be affected with potential repercussions for global fisheries. It’s a shift that stands to alter entire marine ecosystems.

Ocean waters are getting greener at the poles and bluer towards the equator, reflecting what scientists have suggested is a shift in concentrations of chlorophyll produced by phytoplankton – the microscopic marine organisms upon which the entire marine ecosystem food web is based.

Analysing recently published satellite data, scientists have warned that if this trend continues, marine food webs could be affected with potential repercussions for global fisheries. It’s a shift that stands to alter the entire marine ecosystem.

“In the ocean, what we see based on satellite measurements is that the tropics and the subtropics are generally losing chlorophyll, whereas the polar regions – the high latitude regions – are greening,” said Haipeng Zhao, a postdoctoral researcher and lead author on the study.

Since the 1990s, many studies have documented enhanced greening on land, where global average leaf cover is increasing due to rising temperatures and other factors. But documenting photosynthesis across the ocean has been more difficult. Although satellite imagery can provide data on chlorophyll production at the ocean’s surface, the picture is incomplete.

The study – conducted by Nicolas Cassar, the Lee Hill Snowdon bass Chair at Duke University’s Nicholas School of the Environment, and Susan Lozier, dean of the College of Sciences and Betsy Middleton and John Sutherland Chair at Georgia Tech – analysed satellite data collected between 2003 and 2022. It focuses on the open ocean and excludes data from coastal waters.

“There are more suspended sediments in coastal waters, so optical properties are different than in the open ocean,” said Zhao.

The satellite data revealed broad trends in colour, indicating that chlorophyll is decreasing in subtropical and tropical regions and increasing toward the poles. Building on that finding, the team examined how chlorophyll concentration is changing at specific latitudes.

While the researchers observed that out of several variables examined, warming sea surface temperatures correlated with changes in chlorophyll concentration, the authors have cautioned that these findings cannot be attributed to climate change.

“The study period was too short to rule out the influence of climate phenomena such as El Nino,” said Lozier. “Having measurements for the next several decades will be important for determining influences beyond climate oscillations.”

That said, if poleward shifts in phytoplankton continue, they could affect the global carbon cycle. During photosynthesis, phytoplankton act like sponges, soaking up carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. When these organisms die and sink to the ocean bottom, carbon goes down with them. The location and depth of that stored carbon can influence climate warming.

“If carbon sinks deeper or in places where water doesn’t resurface for a long time, it stays stored for much longer. In contrast, shallow carbon can return to the atmosphere more quickly, reducing the effect of phytoplankton on carbon storage,” said Cassar.

Additionally, a persistent decline in phytoplankton in equatorial regions could alter fisheries that many low- and middle-income nations – such as those in the Pacific Islands – rely on for food and economic development – especially if that decline carries over to coastal regions, according to the authors.

“Phytoplankton are at the base of the marine food chain. If they are reduced, then the upper levels of the food chain could also be impacted, which could mean a potential redistribution of fisheries,” said Cassar.

"*" indicates required fields

Printed editions

Current issue

Back issues

Back Issues

Issue 43 Sir David Attenborough’s ‘Ocean’

Back Issues

Issue 41 Holdfast to the canopy

Enjoy so much more from Oceanographic Magazine by becoming a subscriber.

A range of subscription options are available.