Global fisheries bodies 'falling short' ahead of High Seas Treaty

New analysis finds Regional Fisheries Management Organisations are underperforming across key conservation measures, with over half of assessed fish stocks overexploited. The findings come as the UN’s High Seas Treaty approaches enforcement.

The regulatory bodies charged with managing and conserving fisheries across two-thirds of the world’s oceans are threatening marine ecosystems by significantly underperforming, according to an analysis published last month and ahead of the official introduction of the UN High Seas Treaty, a legislative tool that will require deeper collaboration a network of Regional Fisheries Management Organisation.

Published in the scientific journal, Environmental Research Letters, and led by researchers from the Nicholas School of the Environment, the study warns that biodiversity in the high seas in is a worrying state of decline, driven primarily by industrial fishing activities including overfishing and the use of destructive fishing gear.

Nearly 65% of our oceans exist beyond 200 miles of national coastlines. Referred to as the ‘high seas’, these areas encompass big, charismatic migratory animals like whales, sharks and sea turtles, as well as numerous fish species vital to economies and diets around the world.

Regional fisheries management organisations are the primary bodies that regulate industrial fishing and its ecological impact.

“These RFMOs have the dual mandate to ensure both the long-term conservation and sustainable use of high-seas fish populations, which can be migratory animals crossing ocean basins, animals moving between international and national waters, or deep-sea fish,” said lead author Gabrielle Carmine, who completed her Ph.D. in the lab of Patrick Halpin.

Although RFMOs differ in governance structure, each generally has a scientific committee that guides establishment of sustainable catch levels for various species. An independent review published in 2010 found that RFMOs are “failing the high seas” by not achieving their management goals.

Carmine’s analysis adapts and builds on that review. Specifically, her team evaluated 16 RFMOs in 10 categories related to topics such as catch targets, bycatch – unintentionally captured species – and stakeholder involvement, such as Indigenous representation.

For each category, the researchers used publicly available data to grade the RFMO on how well it met criteria associated with 10 questions. Each question was worth one point, with partial credit possible, for a total possible score of 100. What they concluded was ‘widespread underperformance’ with scores ranging from 29.5 to 61.5, averaging just 46.

Researchers now warn that the ecological consequences are stark. In fact, the analysis found that more than half (56%) of fish stocks managed by RFMOs are either overexploited or so depleted they can no longer replenish naturally.

“RFMO performance raises concern about these institutions keeping pace with industrial overexploitation of high-seas marine life and a rapidly changing ocean,” said Carmine.

To that end, the analysis outlines specific areas for policy improvement among RFMOs.

“This review is intended to not just provide a scorecard, but to prioritise areas for constructive improvements in the management of high-seas fisheries and identify gaps in management that need to be filled in the future,” said Patrick Halpin, director of the Marine Geospatial Ecology Lab at the Nicholas School, and who now works as a postdoctoral fellow at Georgetown University.

For example, banning a practice called transshipment – which involves offloading catch onto another vessel that carries it to port – could be one step toward helping to conserve fish stocks, according to the team. Critics of transshipment say it enables illegally caught seafood to enter supply chains across the world, Carmine says.

The team published their analysis around the time that RFMOs typically hold annual meetings to adopt binding management and conservation measures for the following year. For example, the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission, which consists of 26 member nations and oversees more than half the world’s tuna catch, is meeting this week to discuss various topics, including incorporating climate change considerations into fisheries management.

This meeting comes just ahead of official enforcement of a UN agreement for the high seas. The treaty, designed to ensure the sustainable use and conservation of high-seas biodiversity, is slated to come into full effect on January 17, 2026.

“This new UN Treaty requires legal collaboration with RFMOs,” said Carmine. “Perhaps that future collaboration should aim to fill the gaps we found and prioritise long-term conservation.”

"*" indicates required fields

Printed editions

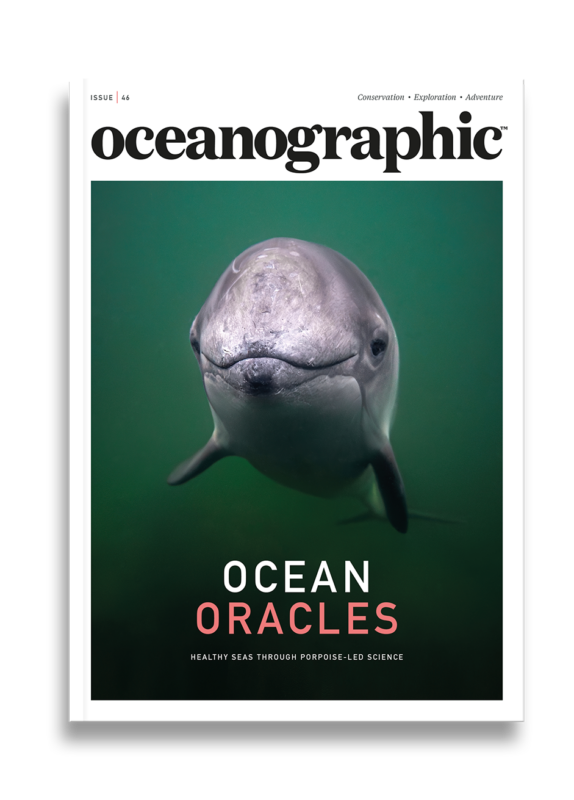

Current issue

Back issues

Back Issues

Issue 43 Sir David Attenborough’s ‘Ocean’

Enjoy so much more from Oceanographic Magazine by becoming a subscriber.

A range of subscription options are available.