Tracking right whales the right way... by thinking small

A new study is helping scientists map the abundance of phytoplankton and zooplankton with greater accuracy than ever before, a development which - in turn - is improving their ability to predict the presence of North Atlantic right whales and their habitats.

Despite being one of the largest animals on the planet, the North Atlantic right whale – with its limited population and vast ocean territory – is also one of the hardest-track. Yet, if we are going to effectively protect their numbers, forming accurate predictions of their preferred habitats is precisely what we need to do.

The best place to start to do this, scientists at the Bigelow Laboratory of Ocean Sciences suggest, is by focusing our sights on some of the ocean’s smallest critters; the North Atlantic right whale’s favourite nibble – the particular species of zooplankton it feeds on.

By considering the daily energy needs of the North Atlantic right whale, a new paper has argued, we may be able to more effectively predict where right whales will be congregating at different times of the year. And all that’s going to take is a better and “more nuanced way” of measuring plankton.

But not only does this research suggest we fine-tune our understanding of the right whale’s prey species but recognise the more complex role that secondary prey species may have to play in the right whale diet, too.

“You can’t protect whales if you don’t know where they are – and they go where the food is,” said Damian Brady, a professor of oceanography at the University of Maine’s Darling Marine Center and a co-author of a new paper pressing the need for that more nuanced data. “This study helps us map that more precisely than ever before.”

Published in the journal Endangered Species Research, this study brings together experts on modelling, right whale physiology, and zooplankton ecology from Bigelow Laboratory, the University of Maine’s Darling Marine Center, the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life at the New England Aquarium, Duke University, and the NOAA Northeast Fisheries Science Center.

When a species – such as the North Atlantic right whale – is hard to track, researchers rely on species distribution models as an important tool for management. Most of these population distribution models account for the abundance of zooplankton that whales feed on. They do this by using indirect measures often taken from satellite data measuring the pigment of chlorophyll across the ocean.

This measurement is then used to estimate the biomass of the kind of plants that zooplankton feeds on, which is then used to estimate the density of zooplankton. It’s something of a flawed system which can lead to inaccuracies in illustrating the presence of particular species of zooplankton – especially the species that North Atlantic right whales like to eat.

“Right whales target only a few key zooplankton species, and their feeding habits vary by location and season,” said Dr. Camille Ross, associate research scientist in the New England Aquarium’s Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life, lead author on the paper. “Replacing prey proxies with direct prey observations tailored to the whales’ foraging requirements has great potential to improve model performance.”

Two years ago, Ross – alongside some of the same co-authors of the newest paper – published the first description of a new and more nuanced approach, interpolating historical observations of the zooplankton species Calanus to create a more direct estimate of their abundance.

In their new paper, the team has taken that work further by expanding the approach to two secondary prey species, which right whales appear to rely on in certain places at specific times of the year, but are less well studied. This data on prey species was collected during the NOAA Fisheries Ecosystem Monitoring Survey.

Using this approach, the researchers significantly improved how well distribution models matched with actual observations by NOAA or right whale movements compared to the models that only included those indirect proxies, such as chlorophyll.

It’s hoped that improving predictive tools with this more direct, accurate information on prey will give scientists more “holistic views” of right whales habitats and how they are using them. This, Ross suggested would be a critical string to the bow when it comes to being more proactive to potential shifts in right whale behaviour as environmental conditions change.

“The key to developing models that will help move things forward is working together with actual users, like NOAA, the Maine Department of Marine Resources, and the fishing and shipping industries,” said co-author Nick Record, a senior research scientist and director of the Tandy Center for Ocean Forecasting at Bigelow Laboratory. “This more direct approach for including prey information is an important step toward meeting those user needs.”

But the value of having better tools for zooplankton distribution goes beyond right whales.

“This paper is specifically focused on a right whale application, but this idea of interpolating zooplankton data from the perspective of the energetic requirements of the predator could be used across marine science,” Ross said. “There are other species, like larval lobster, that feed on Calanus, and there’s no reason that our method couldn’t be extended to those species.”

"*" indicates required fields

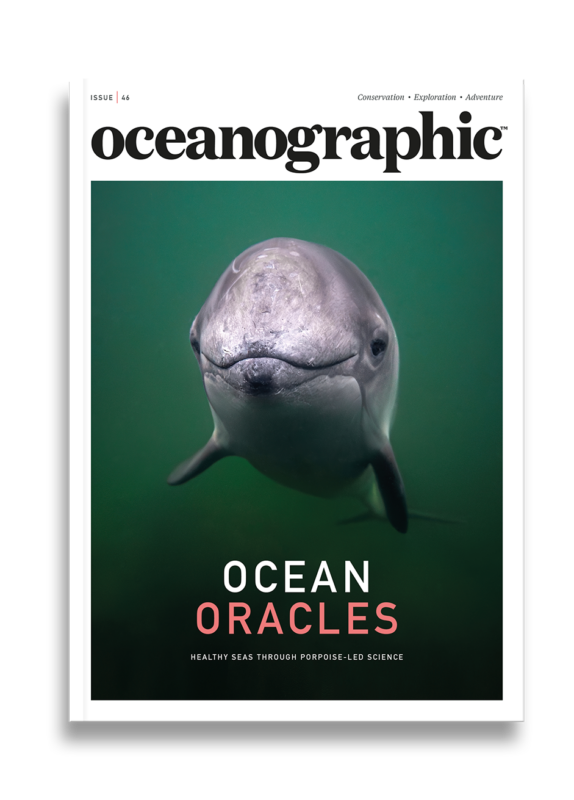

Printed editions

Current issue

Back issues

Back Issues

Issue 43 Sir David Attenborough’s ‘Ocean’

Enjoy so much more from Oceanographic Magazine by becoming a subscriber.

A range of subscription options are available.