Chasing extinction: The search for megalodon

Somewhere beneath all of us, buried in silt or tangled in sediment, are fragments of history just waiting to be uncovered. Objects that haven’t seen daylight in millions of years. Fossils the size of your hand. Relics of forgotten worlds. The Edges of Earth team are hunting megalodons.

As I’ve evolved as a diver, one of my favourite things I’ve learned has been how much you can gain by paying closer attention and what happens when you look closer. If you stay still long enough, or shift your focus to the tiniest detail, rather than waiting for something mega to appear, any experience can become endlessly rewarding.

Even on so-called “uneventful” dives, something memorable always surfaces when tapped into this mindset. It’s been over 500 hours of expedition diving in the last two and a half years, and still, I’m nowhere near tired of it. That’s largely because I’ve learned to treat every dive as its own kind of revelation. It’s where you can slow down, existing uniquely in a slow-paced world in which your sole purpose is to take it all in. And the better you are on your air consumption, the longer this blissful experience can last.

But over time, I started craving more. I wanted each descent to have more of a mission, each with a challenge and end goal. And that’s when the obsession began. That’s when I found myself squarely in the role of an expeditionist. It started with wrecks. I loved the dark, deep, slightly dangerous dives which quickly made me the go-to buddy for penetration sites in Western Australia. Then came the apex predator dives, where I worked alongside scientists collecting data. Then camera work. Then blackwater. Each new challenge pulled me deeper into the sport. But the adventure that hooked me most came from searching for underwater artifacts, or “treasure hunting,” you could call it.

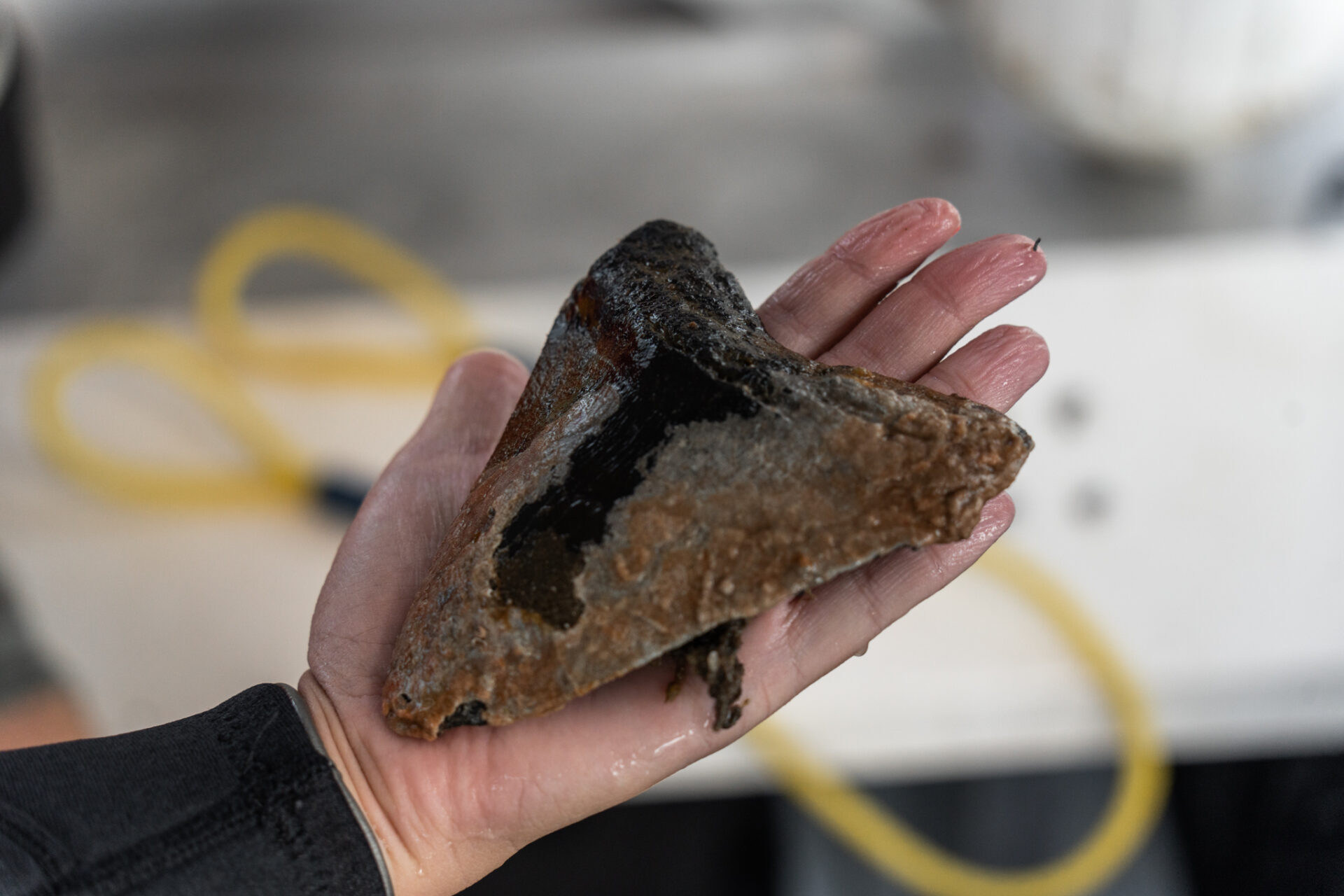

Somewhere beneath all of us, buried in silt or tangled in sediment, are fragments of history just waiting to be uncovered. Objects that haven’t seen daylight in millions of years. Fossils the size of your hand. Relics of forgotten worlds.

This type of exploration rattled my world and allowed diving to take on yet another meaning and purpose. It became about the thrill of the hunt. And it allowed me to slow down even more, pay even closer attention, and lean hard into full-body ocean awareness. Because when you’re searching for these ancient relics, all of your senses need to be entirely honed in. And while so many of my expedition buddies chose to opt out of my murky river dives, or my no visibility sand sifting, I was locked in, hooked on the idea of what history would pop out of the seafloor and just so happen to find my hand.

There’s something wildly humbling about holding a piece of Earth’s story. I mean literally clutching a fossil that predates humans, cities, borders, language like a tooth the size of your palm that once resided in the mouth of creatures we still don’t fully understand. For just a moment, you can feel the immense scale of time settle in your soul. It demonstrates just how small we are, while also rooting our place in something much larger. And of course, it reminds us of how much we don’t know about our home planet. That exploration here actually matters to advance our understanding.

Usually, these artifacts are buried under silt, wedged in rock, disguised as shells or mistaken for a shadow. Even when you know exactly what to look for, the odds are hardly in your favour. To even have a shot, you need to earn it. That means knowing the environment you’re exploring, mastering navigation in total darkness and handling setbacks when things go sideways.

You’ll dive in low vis, face shifting currents, spend long bottom times with no promise of a reward, and most likely, surface empty-handed. But that’s part of the process and you have to love it more than the desired outcome. It also means knowing the rules. Depending on where you are, the artifacts you find may belong to the state, or hold cultural or scientific value that prevent them from being yours to keep.

If what you find contributes to history, you need to know how to handle it responsibly, and be ok with that hard work going towards something bigger than yourself.

But more than anything, you need the right mindset. You need a disgusting amount of patience, and a willingness to get uncomfortable both mentally and physically. You need a team just as obsessed and focused as you are. And you need persistence, because while luck plays a part, finding something rare often comes down to showing up, again and again, until the ocean decides to reward those most invested.

For some people, the thrill is treasure. For others, it’s wreckage, like my friends in Western Australia searching for lost ones. For me, my obsession is remnants of ancient life, specifically fossilised megalodon teeth. To me, these are no ordinary finds. They’re massive, triangular, jet black, and sharp enough to still draw blood. Each one belonged to a predator so colossal it made great whites look small.

Megalodons were the apex of apex predators, dominating the oceans for millions of years. At over 12 meters long, with jaws wide enough to swallow a human whole, they were unmatched in size and power. But around 3.5 million years ago – just before humans – they vanished. No full skeleton has ever been found due to the fact, like common sharks of today, their skeletons are cartilage instead of bone.

What can be found are scattered, fossilised teeth, still showing up in rivers, oceans, and estuaries around the world like breadcrumbs from a vanished era.

And that’s what keeps me hooked, along with the sheer challenge of the dives themselves. You’re often feeling your way across a silty riverbed, relying entirely on texture and shape. When your fingers land on something just right – that smooth, serrated, unmistakable feel – it’s hard not to get emotional and find your heart racing.

Somehow, across millions of years and miles, that tooth ended up right in your hand. A one-in-a-million moment that feels surreal.

Unlike most bones, shark teeth fossilise easily. Some species lose up to 50,000 teeth in a lifetime, dropping one every week as new ones move forward like a conveyor belt. Multiply that across millions of sharks over hundreds of millions of years, and it becomes clear why their teeth are among the most abundant fossils on Earth.

Recent discoveries only deepen the intrigue. In 2023, scientists aboard Australia’s RV Investigator uncovered a deep-sea “shark graveyard” nearly 5,400 meters down, containing more than 750 fossilised teeth, including those from the megalodon’s closest known ancestor. Finds like this help us piece together how these ancient predators lived, evolved, and eventually disappeared.

What’s even more compelling is emerging research suggesting the megalodon may have been warm-blooded, meaning it had an advantage in colder waters but this might have also accelerated its downfall as ocean temperatures shifted. Today, with sharks facing mounting pressures from climate change, overfishing, and collapsing reef systems, these ancient teeth act as biological timestamps, carrying the stories of species that adapted, thrived, and ultimately vanished. If we learn to read them well, they may help us understand how modern marine life can survive the changes coming next.

By now, you’re probably wondering where on Earth does one go in search of these artifacts. Our expedition trail has taken us to fossil-rich waters around the globe, from Australia, the Pacific Islands, Africa, but most notably, back to my home in the USA. Each destination has delivered in its own right, revealing some, for lack of better words, seriously epic relics. But nothing has quite matched the consistency, or the clarity of purpose, as our dives from Florida to North Carolina.

My favourite expeditions, by far and away, have been in Charleston, South Carolina, where the rivers, whose currents will nearly knock you out, hold some of the most concentrated fossil beds in the country. Like much of the east coast, this region was once underwater and was part of a prehistoric marine world where sharks flourished. As the seas receded and time marched on, teeth were buried in sediment, preserved by the unique chemical makeup of the water and surrounding rock.

But in order to explore here, you have to follow strict state rules including obtaining permits to collect. The reason these dives stand out is because of what’s been found and who we’ve found it with. Out here on the Wando and Cooper rivers, the people you dive with matter.

Leading our South Carolina dives was Jeffrey Eidenberger, a Charleston local, U.S. Navy veteran, and SSI Instructor Trainer that runs Carolina Dive Locker, with more than 30 years of diving experience. Then there’s the rest of the dream team – a tactical powerhouse fossil-diving crew composed entirely of ex- and active-duty military divers, including Walker Townsend (a U.S. Coast Guard Master Captain), Jesse Lang (a scuba instructor, commercial diver, and ROV operator who has the side-scan sonar devices to help find fossil beds in the region), Jason Stotko (another instructor with deep technical range), Brian Heinze and Dale Poston (both Assistant Scuba Instructors).

Charleston is our hotspot, yes, but it’s not the only one. Florida’s Peace River, Venice Beach (known as the Shark Tooth Capital of the World), and the Calvert Cliffs of Maryland are all locations ripe for finding. In these places, riverbeds, phosphate pits, and coastal cliffs routinely turn up the sediment bringing teeth into view. The central U.S., now landlocked, was once home to the vast Western Interior Seaway, a shallow inland ocean that bisected North America during the Cretaceous period.

Places like Post Oak Creek in Texas and Shark Tooth Ridge in New Mexico have yielded remarkable specimens. In Minnesota, fossils are in exposed riverbeds and road cuts near ancient shale deposits.

As we face a future shaped by climate change, mass extinction, shifting ocean systems, and lots of unanswered questions about our natural world, these fossils offer data. They’re warning signs and blueprints, each embedded with a record of environmental shifts, teaching us about evolutionary leaps, and survival strategies that span epochs. We’re only now developing the tools to decode that record—to extract chemical signatures and analyze isotopes, allowing us to piece together the habits of long-lost giants.

Studying the past teaches us how species responded to heatwaves or food scarcity, for example. Knowing that sharks have survived multiple extinction events should give us both caution and hope. Because while the planet has always adapted, it’s people, and policy, that now determine the pace of destruction or recovery.

These expeditions are part of a much larger effort to anchor the future in evidence. To collect what we still can, before it’s too late. To involve scientists, passionate divers, professional legends and explorers all together in the work of preservation. And perhaps, most importantly, to remind us that we are part of this ticking timeline too.

Printed editions

Current issue

Back issues

Back Issues

Issue 43 Sir David Attenborough’s ‘Ocean’

Enjoy so much more from Oceanographic Magazine by becoming a subscriber.

A range of subscription options are available.