Fresh water

Freediver Lucie Pollet explores lakes in Switzerland with her camera and finds an abundance of unexpected life.

I remember my first thought when I arrived at the Swiss freshwater lake that my friends had only just discovered: “Wow, this place is beautiful. The water is so blue and clear!” We jumped in the water immediately, only to realise that my initial reaction was completely wrong. The water was foggy because of the high July temperatures. I decided to dive down, to a depth of around 10-15m. After the thermocline, the visibility became clearer and what unfolded in front of me, left me speechless.

After our first freedive session, we explored the lake’s shores. We were surprised to find so many different fishes and species hidden in the reeds, forming schools of different sizes. I was captivated by the lively scenes. My friend suddenly called me: “Follow me! I’m going to show you a wels catfish!” If you say to someone that you dive with a catfish, most people will grimace in disgust. If you search for catfish in newspaper archives, some articles even mention dogs being attacked in lakes by these giant fish. The wels catfish (Silurus glanis) for sure has a bad reputation, but it is a fascinating fish nevertheless as I quickly learned.

The catfish here are not native and threaten the local biodiversity. Experts believe that they were either introduced by humans or that they swam up a river and managed to get into the lake after a flooding event. The catfish have no predators here, and they eat almost anything, including birds. This puts native fish like perch, trout or lake whitefish in danger and scientists are beginning to get alarmed.

Eradicating the wels catfish entirely in most lakes would be impossible but one approach conservationists believe could have a significant impact is to control the population size by fishing. Catching catfish is still not an easy task due to their behaviour, size and weight (an average adult catfish is about 1m long and weighs 10kg). In the canton of Ticino which lies in the Italian part of Switzerland, authorities are contemplating whether to authorise some bigger nets for catching wels catfish and limiting its expansion. Another great idea would be to encourage the locals to eat catfish. This is being done in the Caribbean already where locals consume lionfish, an invasive species threatening local species and ecosystems in the region. In Eastern countries, where the wels catfish originally comes from, its flesh is well-appreciated so it might translate well here too.

My personal experience of freediving with these catfish is a lot different to the negative image this fish has in mainstream media outlets. I was very cautious when I approached a catfish for the first time, but as time moved on, I got to know the individual. I found out where it was resting, how it moved and reacted to us and quickly noticed that it was actually the only fish in the lake that swam and interacted with us. It showed curiosity and its unique character.

I’m a sea lover at heart. I started to scuba dive when I was a child and became a diving instructor for a couple of years. When I lived in Paris and was entirely landlocked, I started freediving on a regular basis to feel closer to the underwater world. Holding my breath and discovering new underwater places became an addiction. My passion for the ocean and the underwater world just kept growing and growing. When a friend of mine, Lyvia, invited me for a freediving session in a lake in the Le Valais region of Switzerland last summer, I could have never imagined that the underwater life in freshwater lakes would be that full of surprises.

We were surrounded by impressive mountains when the large lake lay in front of us. It is around 40m deep and has perfect conditions for a freediving session: No currents, no waves, and the comfort of freshwater. Discovering this lake made me realise that I didn’t have to travel far every time I wanted to enjoy rich biodiversity and beautiful underwater landscapes.

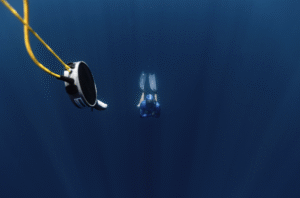

While exploring the lake multiple times, we discovered a very special place; a beautiful succession of immersed trees. It seems to be a meeting place for many fishes. The first time I dove around the dead tree branches, I could see multiple wels catfish hanging out in the deep. I went down slowly, observed them for a while and suddenly saw a big pike emerging that was hiding under the branches. As I was ascending slowly, I suddenly got surprised by a school of giant carps. It felt like I was in the open sea! After the dive, Lyvia told me that in the previous summer, they even saw multiple tiny jellyfish in the lake. She expects them to have proliferated because of the high temperatures that year.

I couldn’t get enough of the lake and its many inhabitants. After many dive sessions in that area, my friend and I started to know more about their habits and behaviour. The catfish seem to love hanging out around the trees where they hide under tree stumps or rest in thick vegetation as if they sometimes long for peace and quiet. Adult pikes are mostly entirely stationary among the tree branches or rest motionlessly on the sand, while younger pikes seek protection around the shoreline. I remember thinking they look like barracudas when I saw my first pike. They are static, calm and tend to become rather large with a common weight of 20kg.

On the opposite behaviour spectrum stand the carps. They swim fast, turn around quickly and swim away from us swiftly. We learned that they don’t like our quick movements and would disappear immediately when we dove down. We noticed that if we dive down, wait and stay static for a while, they might come back to swim closer to us. The more we dove around them, the more they seemed to get used to us.

After my initial lake diving experience, I came back countless times during every imaginable season. In spring, everything comes back to life after a long winter, and we usually have great visibility, while we can observe the fishes spawn. In summer, even though the visibility isn’t as good, the water and outside temperature are comfortable and we can warm up in the sun after each dive – a welcome tradition. Autumn tends to show us various shades of yellow, orange and brown from the surrounding trees, while the visibility becomes better again. From the water, it looks like everything is on fire around the lake. The most challenging season by far is winter due to the low temperatures. The most beautiful thing in winter is when the lake is frozen and the sunbeams come through the thick ice layer on a sunny day. In winter, all fishes hibernate on the bottom where the water temperature is milder and from below the surface, the lake appears to be a magnificent ice desert, surrounded by snow-covered mountains.

Through my adventures, I noticed that lakes are true treasures of biodiversity. While freshwater habitats cover less than 1% of the planet’s surface, they are home to around 10% of described species worldwide. 55% of identified fish species (which translates into more than 18,000 types of fish) can be found in freshwater habitats such as rivers, tributaries, lakes and other freshwater bodies. Unfortunately, one third of these species are endangered because of exploitation, pollution, overfishing, introduction of invasive species and climate change effects. Let’s hope our lakes get more attention and awareness from local populations and public authorities because we urgently need to build a strong and collaborative research and protection framework to uphold the fascinating beauty of these special environments.

Printed editions

Current issue

Back issues

Back Issues

Issue 43 Sir David Attenborough’s ‘Ocean’

Back Issues

Issue 41 Holdfast to the canopy

Enjoy so much more from Oceanographic Magazine by becoming a subscriber.

A range of subscription options are available.