Rainforests of the sea

Even though kelp forests are one of the world's biggest carbon sinks, these special ecosystems are disappearing at an alarming rate. Can a global restoration effort help mitigate the decline?

In the cold depths of the northern Pacific Ocean lies a kingdom swaying to the rhythm of the tides. Beneath its waves you find another world – where towering kelp forests stretch skyward, glinting gold in the watery sun. Seals and otters play ‘hide and seek’ in the dense canopy, and fish dart between the fronds like birds among trees. This underwater habitat creates a home for fish, invertebrates, and marine mammals in their thousands.

In fact, kelp forests harbour a greater variety and higher diversity of plants and animals than almost any other ocean ecosystem and to such an extent that even Charles Darwin himself couldn’t help but wax lyrical about them.

In The Voyage of the Beagle, Darwin wrote: “The numbers of living creatures of all Orders whose existence intimately depends on kelp is wonderful… I can only compare these great aquatic forests… with the terrestrial ones in the intertropical regions. Yet if in any country a forest was destroyed, I do not believe as many species of animals would perish as would here from the destruction of kelp.”

Darwin’s awe for the abundance of life found in kelp forests emphasises the significance of these underwater ecosystems. Kelp forests are home to an astonishing array of marine life, providing habitat and sustenance for over 800 species of fish, invertebrates, and marine mammals. While Darwin’s observations reflect his awe at the abundance of kelp forests off the coast of South America, these underwater forests – dominated by large brown seaweeds that thrive in cold, nutrient-rich waters – grow in temperate zones across both hemispheres, lining about a quarter of the world’s coastlines. In fact, around 740 million people live within 50 kilometres of these underwater ecosystems. These prolific underwater forests grow at rates of up to 45 cm (18 in) per day, making them one of the most productive ecosystems on Earth.

Kelp forests not only create a thriving habitat but also serve as an ecological powerhouse that underpins the health of our oceans. Harvested for centuries, kelp serves as food, fertiliser, and a nutritional supplement, supporting both human and marine life. These vibrant underwater forests provide essential shelter and nourishment for a multitude of commercially important fisheries like cod, rockfish and abalone.

They also protect coastlines from erosion and contribute to global environmental health. The value of the ecosystem services offered by kelp forests is estimated to range between $500,000 and $1,000,000 per kilometre of coastline, underscoring their significance to both nature and society.

Perhaps most impressive of all these ecosystem services is the ability of kelp forests to sequester carbon. Measuring carbon sequestration by kelp forests has historically posed challenges, but a recent study by Conservation International reveals that their capacity for carbon absorption has been “grossly underestimated”. This study suggests that kelp and seaweed forests sequester as much carbon as the Amazon rainforest. Published in Biological Reviews, the research estimates that the protection, restoration, and improved management of kelp and seaweed forests could yield mitigation benefits of up to 36 million tons of CO2 – equivalent to the carbon-capture ability of 1.1 to 1.6 billion trees.

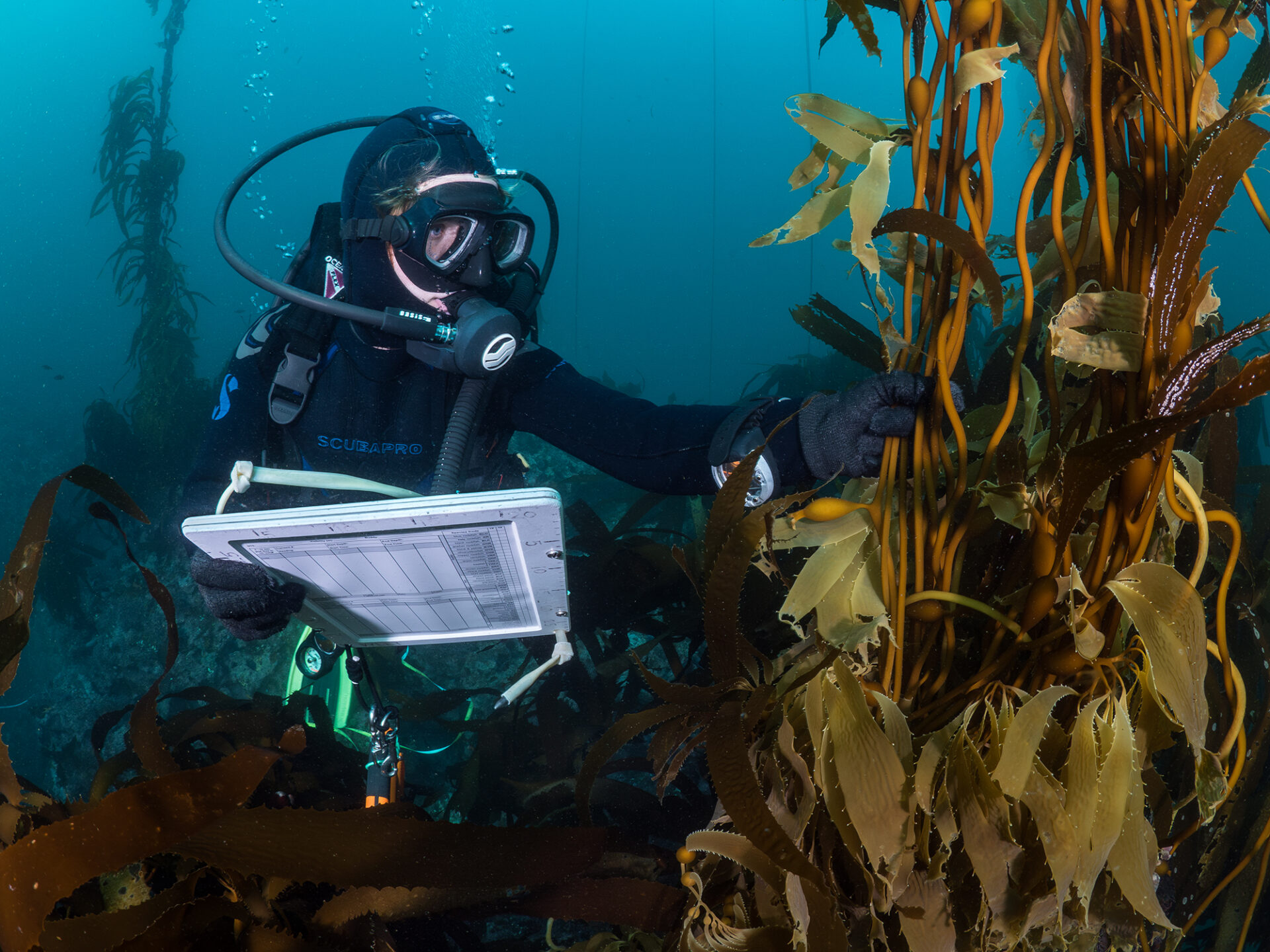

However, this highly productive ecosystem is not without its vulnerabilities. In temperate oceans across the globe, this vibrant realm – once a thriving underwater wilderness – is disappearing due to warming waters, over-harvesting by fisheries, and overgrazing by local predators. Now scientists, indigenous groups, and local communities are racing against time to revive these underwater forests. From the rugged coastline of British Columbia to the Sussex coast of England and the shores of Tasmania, a global movement is rising to restore what has been lost – and in doing so, rekindle the health of our oceans and ultimately, our planet.

A quarter of the world’s kelp species flourish along North America’s Pacific coast, but alarming reports show that 95 percent of these underwater forests have vanished in just seven years. A sea star wasting disease that began in 2013 decimated their populations, causing a mass die-off of sunflower stars, an important resident in the kelp ecosystem for their regulation of kelp’s main grazer: the purple sea urchin. The loss of urchin predators led to an explosion in sea urchin populations. Now these voracious kelp grazers have mown down kelp forests, wreaking havoc on the kelp forests from Monterey Bay California to Vancouver Island, British Columbia.

Up and down the coast, researchers, local indigenous communities, and fishermen are pioneering methods to restore lost kelp populations. These efforts include cultivating heat-resistant varieties and experimenting with innovative transplant techniques using various materials for anchoring. Initiatives are also underway to restore sun star populations, urchin culling and incorporating the small purple urchin into local cuisine.

On the other side of the world, where the northeastern Atlantic meets Europe, the coastline once hosted boundless underwater kelp forests, but unsustainable trawling practices have since degraded the sea floor to a barren wasteland. However, on England’s Sussex coast, a 2021 bylaw has sparked significant kelp restoration efforts. The Sussex Nearshore Trawling Bylaw established one of the UK’s largest trawling-free zones, aiming to reverse the damage done by trawling practices that combined with storm surge wiped out 96% of the region’s kelp forests since the late 1980s.

In the wake of the bylaw, the Sussex Kelp Recovery Project, was established in an effort to monitor the recovery of kelp forests along the Sussex coast. The rewilding team, bolstered by local support have been monitoring the coastline for signs of regrowth and establishing a baseline for future growth measurements. While initial data suggests that kelp recovery has been slow, the surrounding ecosystem is rebounding more quickly, with local divers and fishermen noticing the return of mussel beds, dolphins, and rays.

Restoring Sussex’s kelp beds to historic levels could bring immense benefits, with an estimated ecosystem service value of £3.63 million annually. This includes enhanced coastal protection, fisheries, and tourism, compared to today’s sparse kelp beds, which provide limited economic value and primarily contribute £30,861 in coastal defense.

In Tasmania, the giant kelp forests of the Southern Ocean are under severe threat due to ocean warming, which has caused their rapid decline. To combat this, researchers at the University of Tasmania are exploring innovative restoration techniques, such as breeding heat-resistant kelp varieties. The Nature Conservancy is also involved in efforts to restore these critical underwater ecosystems. Together, these initiatives aim to revive Tasmania’s kelp forests and mitigate the damaging effects of climate change on this region’s marine biodiversity.

Back in South America, in the waters where Charles Darwin first marvelled at kelp forests, a remarkable restoration story is unfolding. Argentina’s Peninsula Mitre, now a protected area, safeguards over 30% of the country’s remaining kelp forests. This region serves as one of the last global sanctuaries for kelp forest ecosystems, hosting large populations of seabirds and marine mammals, with high biodiversity due to unique species and high endemism and serving as one of the last untouched havens for giant kelp, a species that captures carbon at rates ten times higher than tropical forests. The waters around Tierra del Fuego and Isla de los Estados are crucial spawning and nursery grounds for fish species harvested elsewhere in the Argentine Sea. As conservationists work to preserve this vital ecosystem, Peninsula Mitre represents a beacon of hope, demonstrating how these underwater forests can help in the global fight against climate change.

Beneath the surface, kelp forests are silently fighting for survival, but the story doesn’t end in decline. Across the globe, communities of researchers, citizen scientists, and local conservationists are breathing life back into these underwater forests. From selective breeding programs to efforts to rewild lost ecosystems, the solutions are many, and the hope is real. As fragile as kelp forests may seem, they are also incredibly resilient. Every local effort to restore them sends ripples of impact, proving that with care and cooperation, the ocean’s forests can flourish once again.

If you’re feeling inspired to help protect kelp forests, here are a few ways to make a difference:

- Support Restoration Projects: Contribute to organisations focused on restoring kelp forests, look for local initiatives within your region.

- Advocate for Marine Protection: Encourage policies that safeguard marine ecosystems and reduce harmful activities like overfishing and trawling.

- Reduce Your Carbon Footprint: Since ocean warming threatens kelp forests, cutting down on energy use and supporting renewable energy helps fight climate change.

- Spread Awareness: Share the importance of kelp with your community to inspire more people to take action.

Printed editions

Current issue

Back issues

Back Issues

Issue 43 Sir David Attenborough’s ‘Ocean’

Enjoy so much more from Oceanographic Magazine by becoming a subscriber.

A range of subscription options are available.