Mexico: "Goals met" to protect last eight vaquita from extinction

Mexico's vaquita have - over the last two decades - suffered a population decimation resulting primarily from entanglements in Mexican fishing gear used to illegally and indiscriminately harvest the also endangered totoaba fish.

The Mexican government claims to have fulfilled objectives set out in a 2023 action plan created to protect the critically endangered vaquita porpoise and the country’s iconic, resident fish – the totoaba, in a move it has hailed “symbolic” of a commitment to both environmental conservation and international compliance.

The measures taken include both public education and awareness programmes to encourage legal and sustainable fishing within key Mexican waters and a raft of enforcement measures, including an increase in land inspection and surveillance activity across the breadth and depth of the domestic fisheries value chain.

In implementing these measures, the government’s aim is to crack down on the illegal and indiscriminate fishing of totoaba, a prized catch for which demand has skyrocketed on the black market in the last 20 years, and reverse the fate of the critically endangered vaquita, a species whose severe decline is inextricably entwined with the practices used to fish the totoaba.

The vaquita is one of the world’s most at-risk marine species. At last count, according to results from a survey carried out in the summer, there are now only eight individuals remaining in the wild, a drop from the 10 to 13 individuals estimated in 2023.

Vaquita – a species of porpoise living solely in the Northern Gulf of California – have, over the last two decades suffered a population decimation resulting primarily from entanglements in Mexican fishing gear used to illegally harvest the also endangered totoaba.

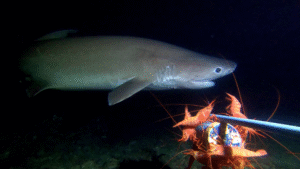

The totoaba, meanwhile, is a large, slow-growing fish found exclusively in the Sea of Cortez where it is capable of reaching over six feet in length and weighing up to 220 pounds. Once abundant in the region, overfishing and habitat degradation has led to their own dramatic decline, pushing the species to the brink of extinction.

Together, the totoaba and the vaquita share a tragic connection. Driven by an insatiable demand on the black market for totoaba swim bladders for use in traditional Chinese medicine; unsustainable, indiscriminate, and illegal fishing practices have proven deadly for both species.

In fact, the pair’s plight has given rise to the term “dual extinction”, a tragic ending that awaits both the totoaba and the vaquita should the crisis go unaddressed.

Mounting pressure applied to the Mexican government which includes both lawsuits and sanctions from international conservation groups has forced the country to face the issue directly and increase enforcement to protect the two dwindling species.

In 2023, US Customs and Border Protection officers seized $2.7 million worth of totoaba swim bladders that were being illegally transported through the US state of Arizona. Earlier that same year, the Secretariat to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) sanctioned Mexico for failing to adequately address its illegal fishing issues.

In response, the Mexican government finally adopted an action plan in 2023 to tackle illegal fishing and protect its last remaining vaquitas.

Mexico’s National Commission for Aquaculture and Fisheries (Conapesca) has now claimed that the goals and projects of that action plan have been fulfilled. Over the last two years, the agency has held multiple information workshops to encourage legal fishing activities. They have also provided guidance to inform local fishers about illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) regulations.

In terms of enforcement, the government has now established more than 730 random checkpoints, with inspections carried out throughout the value chain, including at warehouses, collection centres, freezers, fish markets, and restaurants. These actions included the inspection of more than 5,190 small vessels upon departure and arrival, and the destruction of more than 38,000 metres of prohibited gillnets and 30 traps and cages.

An Alternative Fishing Gear Programme has also been established while more than 230 commercial-fishing permits for alternative fishing gear have since been issued.

The agency has also increased registration to better track who is legally participating in area fisheries and is working with the Mexican Navy to develop a remote monitoring programme that can ensure small vessels are not operating in protected areas.

To ramp up its efforts, the Mexican Navy has partnered with the independent conservation group, the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society on preventing illegal fishing in the Northern Gulf of California, using enforcement vessels and surveillance drones in the region to prevent IUU fishing and remove gillnets from the ocean.

A focus for 2025 will be to expand on this partnership as the Sea Shepherd looks to refine the tools being used and take the protection model into other critical areas.

In a post issued via its website, Sea Shepherd, said: “With plans to extend operations to Scorpion Reef and beyond, Sea Shepherd and the Mexican government are setting a new benchmark for marine conservation. This collaboration proves that with the right tools, expertise, and partnerships, illegal fishing can be confronted – and ecosystems can be defended.”

"*" indicates required fields

Printed editions

Current issue

Back issues

Back Issues

Issue 43 Sir David Attenborough’s ‘Ocean’

Back Issues

Issue 41 Holdfast to the canopy

Enjoy so much more from Oceanographic Magazine by becoming a subscriber.

A range of subscription options are available.