New 'forever chemicals' found in killer whale blubber

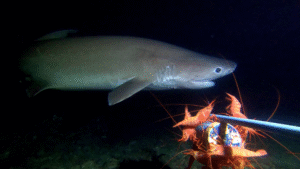

Unlike well-studied PFAS, which typically accumulate in protein-rich tissues such as liver and blood, these new substances accumulate in fat-rich blubber, leaving whales and other species of marine life particularly vulnerable to their exposure.

In the same week that global discussions to develop a legally-binding multilateral Plastics Treaty to tackle the plastic pollution, microplastics, and their associated harmful chemicals crisis collapsed, scientists identified a class of PFAS in the blubber of killer whales that had previously gone undocumented.

The new study – published in Environmental Science and Technology Letters – details the presence of five fluorotelomer sulfones (highly fluorinated, fat-loving chemicals) never before reported in wildlife. And it would appear that whales and other marine mammals could be particularly vulnerable to their exposure.

That’s because, unlike well-studied PFAS, which typically accumulate in protein-rich tissues such as liver and blood, these new substances accumulate in fat-rich blubber.

“This is the first time that highly fluorinated PFAS have been shown to preferentially accumulate in fat,” said lead author, Mélanie Lauria, formerly a doctoral student at the Department of Environmental Science at Stockholm University and currently at the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology.

“It challenges the long-held assumption that PFAS primarily bind to proteins and accumulate in the liver of blood. Research has so far focused on a subgroup of PFAS that is ‘charged’ or ‘polar’, and therefore interact mainly with proteins.

“The results of this study show that we have overlooked PFAS that are neutral and can interact and accumulate in neutral fats such as blubber.”

Researchers were able to analyse tissue samples from killer whales in Greenland and Sweden. The newly identified compounds accounted for up to 75% of fluorine-containing substances in blubber, but were undetectable in liver tissue – evidence of their ‘fat-loving’ nature.

“These findings suggest we may be underestimating the PFAS body burden in marine mammals. Blubber can represent up to half of a marine mammal’s body mass, so neglecting fat-soluble PFAS could significantly undermine the accuracy of exposure assessments,” said co-author Jonathan Benskin, professor at the Department of Environmental Science, Stockholm University.

The study has raised new questions about chemical exposure in apex predators, with implications for environmental and human health – particularly in Arctic regions where marine mammals are part of traditional diets.

PFAS stands for poly- and perfluorinated alkyl substances and is a collective term for a large group of man-made chemicals that have widely used in various industrial and consumer products since the 1940s. These harmful chemicals are often used in conjunction with plastics for their water-repellency among other properties.

In 2021, researchers at the University of Birmingham investigated the environmental effects of microplastics and PFAS to show that, when combined, they can be very harmful to aquatic life. PFAS and microplastics are both known as ‘forever chemicals’ because they do not break down easily and can build up in the environment, leading to potential risks for wildlife and humans.

Both PFAS and microplastics can be transported through water systems on long distances, all the way to the Arctic. They are often released together from consumer products.

The research paper, ‘Discovery of Fluorotelomer Sulfones in the Blubber of Greenland Killer Whales (Orcinus orca)’ is now published in Environmental Science and Technology Letters.

"*" indicates required fields

Printed editions

Current issue

Back issues

Back Issues

Issue 43 Sir David Attenborough’s ‘Ocean’

Back Issues

Issue 41 Holdfast to the canopy

Enjoy so much more from Oceanographic Magazine by becoming a subscriber.

A range of subscription options are available.